In the field of medicine, it can manufacture fully customisable artificial limbs. In catering, it could expedite the delivery of food. And in creative spheres, it promises to change the face of art – quite literally!

3D printing – also known as additive manufacturing – has been around for decades but has slowly moved towards the mainstream as it becomes increasingly commercialised. A number of sectors have found ways it can benefit them but what use is 3D printing currently having on railways around the world?

The United States of America

Rail freight operator Union Pacific (UP) first experimented with 3D printing in 2013. Back then, it created a handheld automatic equipment identification (AEI) device, which is used to track rolling stock and make sure it’s assembled in the correct order. Early prototypes were fragile but UP has stuck with the technology and continues to embrace it four years down the line.

“Today, we’re using tougher plastic, allowing 3D printed parts to be dropped or treated like any other piece of equipment,” says UP’s senior system engineer Royce Connerley. “It’s critical in a railroading environment.”

In a basement room of UP’s Omaha headquarters, in Nebraska, the company’s 3D printer runs constantly. The process begins when engineers createe a virtual design of the object they want to create using computer aided design (CAD) software. From there, the process is as easy as clicking file and print, according to UP. Once it’s finished, the product needs to be cleaned before it’s ready to be used.

Printing 3D parts in-house has accelerated UP’s rate of change by removing the need to go back and forth with an external party. Connerley says design tweaks can be made, and new 3D parts printed, “within hours”.

Follow Global Rail News on Facebook to receive updates throughout the day

UP’s 3D printer is playing a critical role in machine vision, the company’s automatic laser inspection system. Using the printer, the team at UP designed a crucial component that blows air across the laser for cooling and provides outward air flow to keep debris out.

The operator says that 3D printing gives it “a competitive edge” and “room to experiment in ways never previously dreamed”. For now, it seems the technology is just used for experimental purposes but it is still in its relatively early days.

Great Britain

In England, Scotland and Wales, the arms-length public body Network Rail owns and operates 20,000 miles of track but 3D printing currently plays no part in its maintenance operations, according to a spokesperson.

That does not mean, however, that 3D printing is not being talked about in the country’s industry. A group of researchers from the University of Birmingham is looking at using it to automate inspection techniques, adding material back onto the surface of wheels to repair damage as it’s detected.

The group is assessing the feasibility, so it’s still in its early stages, but it has the potential to reduce train maintenance costs by reducing inspection times and extending the life of wheelsets.

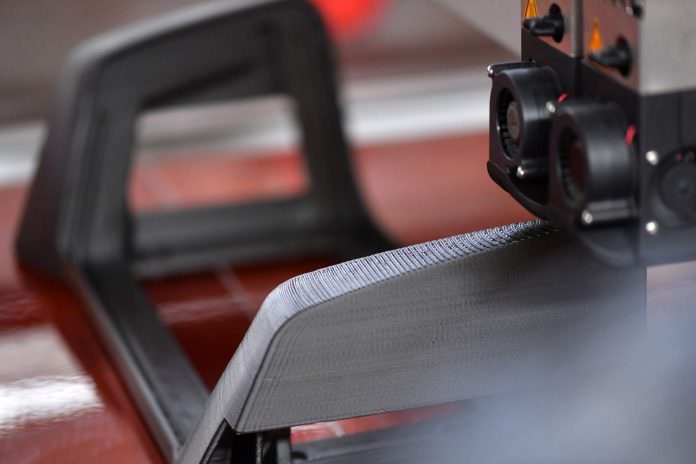

The construction of a headrest using a 3D printer:

Germany

From headrests to ventilation grilles and braille signage, Deutsche Bahn (DB) – the largest railway operator in Europe – has already made 1,000 spare parts using 3D printers. It expects that number to double by the end of 2017 and has even more ambitious plans for 2018, planning as many as 15,000 components.

The first spare part was a coat hook made of plastic but now metal items are also being produced. Using this technology, DB has even been able to fabricate terminal boxes for Germany’s high-speed ICE trains.

Not only is it more flexible and cheaper, says DB, but faster too, expediting the production of spare parts to get trains back operating as soon as possible.

Meanwhile, in the Bavarian city of Erlangen, Siemens has opened up an additive manufacturing centre which continuously produces spare parts to specification for the railway industry.

Instead of weeks or months, the production and delivery time is shortened to days, all without the need for ordering a minimum amount.

Around 460 spare part models are ‘stored’ in its virtual warehouse but, in the future, Siemens wants to reduce the amount of stock, saving on storage costs in the process.

The municipal transport company in Ulm, Germany, has been one of the beneficiaries. After the company launched a small fleet of Siemens Combino streetcars in 2003, several streetcar drivers said they would like to have additional switches on the driver’s seat armrest for the turn signals and for setting switch rails. But, because the number of units required was very small, conventional manufacturing methods would have been impractical. Thanks to a digital model of the armrest, Siemens announced in April 2017, that it was possible to redesign it with cavities into which switches could be installed.

In addition, it is also possible to remanufacture parts which are no longer available off the shelf.

Some items are too big to be made inside the chamber of Siemens’ 3D printer but a part can sometimes be assembled through a number of smaller components.

The above is but a snapshot into how the industry is adapting to 3D printing. As it becomes cheaper, more accessible and as its applications grow in number, 3D printing could revolutionise the means of production and, who knows, one day we might see passenger trains being made in factory-sized 3D printers.

Read more: Union Pacific’s new bridge monitoring tool has the ‘potential to revolutionise’ bridge inspections